The Overton Window of a Product

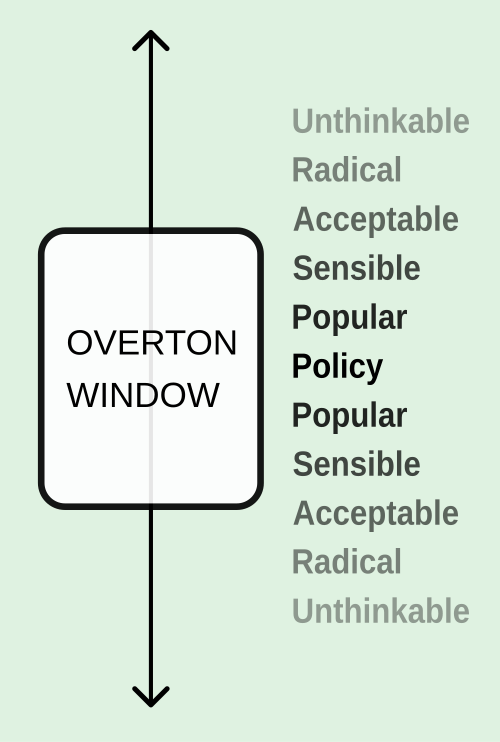

The Overton window, aka the window of discourse, is the range of ideas acceptable to mainstream thought. It is named for Joseph P. Overton, who stated that whether an idea was politically viable depended more on whether it fell in this range than on the politicians in office. [Wikipedia]

Despite its origin in politics, I’d argue this concept also applies to product management:

- At a macro-level, PMs are trying to launch innovative products that both push the industry forward and spark delight in your users.

- At a micro-level, PMs are marshaling resources to achieve their vision, either by pitching executives to get top-down resource allocation or by coaxing bottom-up buy in from line-level engineers.

Whatever the case, that vision had better be palatable to your stakeholders. And what is palatable — within the Overton window — will change with time.

“Observe due measure, for right timing is in all things the most important factor.” - Hesiod

Understanding the window allows you to better time and prioritize your launches. Here are 3 questions to check where a product idea falls relative to it:

- Is the technology ready for production?

- Is the organization strategically ready to launch this?

- Will users accept it? “Is the market ready?”

You want to time the product so it launches just as all 3 questions turn to “Yes.” Otherwise, the product might end up as “an idea ahead of its time.” (not speaking from personal experience or anything…)

So how do you sanity check these questions? Floating the high-level idea across engineering, leadership, and target users does the trick:

- The pushback from engineering gives a sense of the technological window.

- The enthusiasm (or lack thereof) from leadership tells you where the company is strategy-wise.

- A quick user study will tell you if the market is ready to accept this product.

To give a recent example from my work - while researching a project I found that while the market and the strategy were ready, the technology was still a year behind. So I decided to delay it for a year. Our client was temporarily unhappy, but afterwards everyone came back more amenable to the idea, we will have much less technical debt for it.

In summary, doing this sanity-check before building a product will save you headaches in the long run.

Case study: Google Glass

Now, this was certainly a product ahead of its time. The Google Glass first launched in 2013, targeting a mass consumer market.

Is the technology ready for production?

I tried the Google Glass v1 early on in its product life, and even then it was clearly not ready to be a mass consumer product. For one, the battery life was dismal. For another, the screen itself was tiny and caused eyestrain to use. The skewed weight distribution made it hurt to wear for long periods. And there was no hero use case for a general consumer to be interested in.

Is the organization strategically ready to launch this?

This is debatable. The Glass did fit into Google’s nascent hardware story. But the Google One strategy hadn’t yet emerged, which left the Glass without a strong consumer use case.

Are users willing to accept it? “Is the market ready?”

A resounding NO.

The first Google Glass launched in 2013 when antipathy against Google was at its peak, back when San Francisco residents were attacking shuttle buses and harassing employees on the streets. In this climate, the Google Glass wearing “Glassholes” became the symbol of privacy invasion and gentrification rolled into a single, highly-visible product.

Outcome

Glass launched to derision of epic proportions. Since then, the team and product have pivoted to focus on industry use cases, where it does check the boxes of the Overton window:

- the technology has matured since its first launch

- the industrial market is more accepting of strange-looking gadgets with very specific use cases.

Still, I predict that Google Glass for consumers will return one day. When it becomes indistinguishable from normal glasses, and privacy regulation is ready for omnipresent cameras - that is when the Overton window for Glass has arrived.

This brings us to another concept — actively moving the window, instead of waiting for it to arrive.

Moving the window

“Luck is a matter of preparation meeting opportunity.” — Oprah Winfrey

Back in Overton’s political world, activists are the ones moving the window. Through telling stories, generating media attention, and passing cutting-edge policy at a small scale, they are constantly pushing the boundaries of what is acceptable to the mainstream. By this theory, elected officials only write public sentiment into legislation only after activists push the window into view.

This is akin to building sentiment towards a new product idea - only instead of passing local legislation, we first build up the infrastructure by launching proofs of concepts. This way, the team is ready to productionize as soon as the window arrives.

Depending on what’s holding the window back, you might use different tactics to move it:

- Engineering - you might either build a proof of concept or launch an intermediary product that builds up the tech stack.

- Business strategy - depending on the size of the gap, shifting strategy can be as simple as a series of pitches, or as hard as a decades-long roadmap with intermediary launches to build up your talent. A common example is merging 2 projects (or companies!) - it takes time, but you’ll end up better positioned in the long run.

- Users - Again, depending on how big the gap is, this can either be as small as a marketing campaign, or as big as releasing stepping stone products until your original idea becomes “innovative” instead of “alien.”

So even if your product vision is unpopular right now - hold on to it. Keep refining the idea and working the window. In fact, pushing the window can even give you control over market timing, as we explore in the following case study.

Case study: Apple iPhone

This is a superb example of moving the window towards a particular vision.

At the industry level, we were moving towards a portable phone device, and each generation of product laid the technological foundation that the next one used.

But on a personal level, Steve Jobs made it his mission to make sure the smartphone was the touch-screen experience we take for granted today.

It was a tall ask on all fronts. Prior to the iPhone, users thought of phones as devices with buttons you can press. Personal computers were coming into the mainstream. Capacitive touch screens were a brand new technology that hadn’t matured to the level needed for a consumer product. And the Palm Pilot was the standard for PDAs. How could Jobs convince everybody to buy this slab of glass and metal over the alternatives?

Jobs started by aligning everyone in the company to his vision. He wanted to stand out from other stylus-driven PDAs, so he killed the Apple Newton product. He steered the company away from the touchscreen tablet they had been prototyping and convinced them to build a phone instead.

Meanwhile, Apple piggybacked off an adjacent trend - MP3 players. But instead of putting out sticks with buttons like everyone else, they embedded touch-sensitive controls and eventually screens into the iPods. This product line built up the technology needed for the iPhone and got users used to toting screens around in their pockets. It also targeted a young, trendsetting demographic, to make sure there was a ready audience for iPhone’s first launch.

By being the one pushing the window, Jobs controlled the market timing and claimed the first-mover position. The rest is the stuff of product legend.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: